Watch and Clock Repair Blog

The History Of The Cornell Watch Company

Over 150 years ago, in 1870, Paul Cornell, a real-estate dealer, teamed up with J.C. Adams who was a noted watchmaker at this time. Together, they organized The Cornell Watch Company.

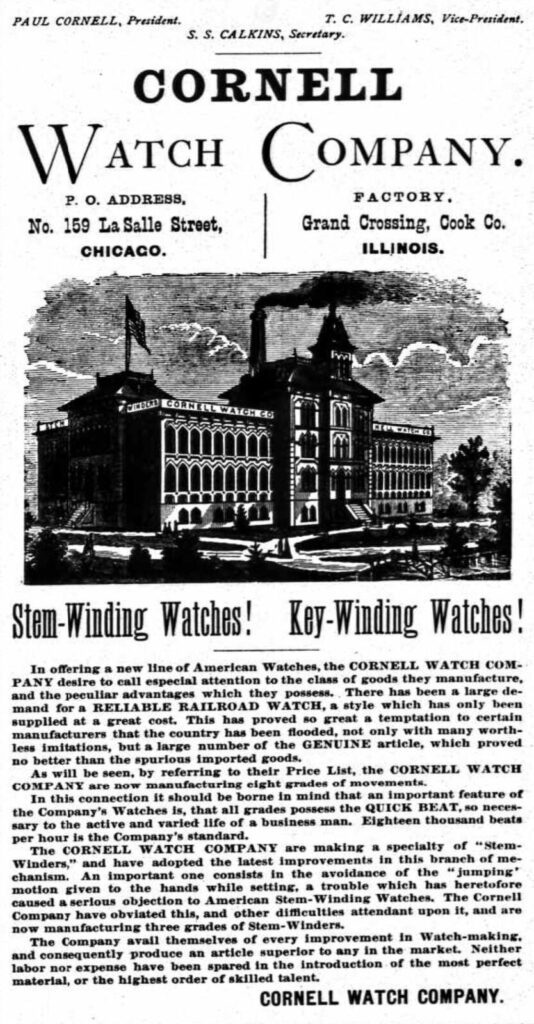

With grandiose plans, in 1871, they constructed a factory in Grand Crossing, Illinois, for the cost of $400,000, (approx. $10 million dollars today) The factory was plain but substantial with a brick structure containing one main building and two additional wings. This 4-story high structure was completed with a tower and bell. There was enough space to house 500 workers.

The entire first floor of each wing was dedicated to the machinery department, but without equipment, they then had the arduous task of manufacturing the very machines that would occupy this department before they could start the manufacturing process for their watches.

As challenging as this was, when finished, these machines were considered top of the line, in their day. Machines would cut the heaviest of metal or shave off thin ribbons of metal so delicate they may fall apart at the touch. During this time, their master machinist, who supervised 19 machinists at the highest degree of proficiency, invented a planer for the operation that could be used at any angle, using setscrews graduated at different degrees. A 30-horse-power engine was used to power these machines.

Next up, the plate room. Plates formed the frame of the watch and were punched out of high-quality brass. The plates would be pierced a specific number of times, to house the train of the watch. All of the wheels and other brass fixtures for the watches were also fabricated at the factory.

The balances were made from a combination of brass and steel and with a beautiful, delicate finish. Being in Chicago, with their variant temperatures, the added layer of the dual metals (which have different reactions to cold and heat, so they effectively balance each other out) neutralize one another. Because of this, the balances used by the Cornell Watch Company had less instances of contraction and expansion when moving between extreme temperatures.

Their entire staff, around 200 workers, reviewed their work for blemishes. The dials, hands, regulators; even the screw sets were inspected to ensure standards were upheld. Early on, the factory was moving 25 watches per day.

By 1873, Cornell claimed that its railroad watch was the one to beat, claiming superior parts and having perfect escapements. Their watches sold complete with a certificate boasted a frequency of 18,000 beats per minute guaranteeing a railroad standard of accuracy. Within the first 18 months, the workforce increased to a whopping 500.

A savvy marketing ploy was added, the company chose only one jeweler in each town to exclusively sell their timepieces – a specialist, like a representative for company.

Despite the company’s growing success, Cornell decided to roll the dice; the company abruptly left Chicago and moved operations to San Francisco, California. Most machinery was sold off to a new startup, the Rockford Watch Company of Rockford, Illinois. In November 1874, starting over – the company fronted the expenses for 40 men plus their wives and children to relocate with the company, with the stipulation, of course, that they would pay back these costs in monthly installments.

This left their building in Grand Crossing to be purchased by the Wilson Sewing Machine Company, who later added to the building, creating an even more expansive manufacturing depot.

With this move, the company would have several new advantages; the stable climate of California would increase efficiency, streamline manufacturing and increase operational space to allow them to start producing cases for all their watches in house. They were also looking to cut costs – by utilizing California’s Chinese labor, as Chinese workers were equally as efficient, while willing to work for much lower rates than their American counterparts.

The move to Chinese labor, however, failed. The company faced incredible backlash from the public, the papers noting protests in opposition to the employment of foreigners over Americans. In reaction, the company started laying the Chinese off, day to day, to help dispel the public unrest, without success, and the company started again, re-incorporating under the name The California Watch Company.

In 1876, after suffering from financial and reputation issues, the California Watch Company ceased operations. In 1899, the factory, in Berkeley, built by the California Watch Company was destroyed by fire.