Who Invented the Clock?

When thinking about the invention of the first clock, people often question: “How did the first clockmakers know what time it was without a clock?”. Well, before mechanical clocks were invented there were many other methods used for measuring time. Following patterns in the cosmos and relating them to our daily lives lead our ancient ancestors to map the cycle of each day, month, and year eventually lead to building timekeeping devices of all sorts.

The invention of the original clock(s) is hard to nail down as they were a progression of human ingenuity over time rather than a single discovery. And answering the question of who invented time is impossible, as not only was time not truly invented, but it’s impossible to pinpoint who first began measuring time in different parts of the world.

Here we will talk about who made the clock by discussing some of the people involved in the process of building the clock from the ancient methods of timekeeping.

Who Invented the First Clock? History of Timekeeping

Ancient Timekeeping

Before the first clock was made, there was recognition of the need to measure time and different cultures had different approaches. So, we can’t say who discovered the clock as timekeeping technology evolved over time from these ancient devices that often relied on natural indicators of time.

So, what did ancient timekeeping look like?

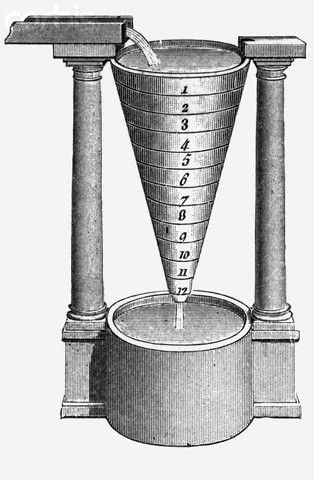

Sundials, used as far back as 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt, were among the first devices to measure hours by tracking the sun’s movement. Water clocks (or clepsydras) were also significant, with early versions appearing in Babylon and Egypt around the same time.

Water clocks operate by regulating the flow of water into or out of a vessel, with the water level marking the passage of time.

Since shadows were hard to measure on cloudy days, and water wasn’t always an abundantly available resource, other forms of ancient clock tech emerged from older civilizations. Two examples that stand outare the candlestick clock and the hourglass.

Being the more common of the two, the hourglass is still used as a symbol for the passage of time. Being much akin to its water clock predecessor, the hourglass uses volumes of matter, dispersed between two chambers, to show the relative passage of time.

In contrast, the candlestick clock utilized a different method from the hourglass and water clocks. With these timekeepers, a candle would be lit beside an evenly spaced series of markings. As the candle burned down, the height of the candle—relative to the markings—would show the passage of time. Considering other timekeeping methods required outdoor use, this clever piece of ancient clock tech was more pragmatic during inclement weather.

Invention of Mechanical Clocks

The first mechanical clock is credited to the medieval period, around the 14th century. These early clocks, primarily found in European monasteries, were weight-driven and regulated by escapements. They were not designed for accuracy but to signal prayer times, so they didn’t even have minute hands. A notable early example is the clock at Salisbury Cathedral, built around 1386.

These first mechanical clocks used the Verge Escapement movement. This key innovation helped clock-making flourish—utilizing a balance wheel to help keep time moving forward.

In the 1400s, spring-driven mechanisms replaced weights, which became the basis to build the first pocket watches.Peter Henlein, a German locksmith, is credited with creating some of the first portable mechanical watches in the early 1500s. These were known as “clock-watches.” By the 17th century, pocket watches became more common, thanks to advancements like the balance spring.

In 1656, Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock which also played a significant rrole in increasing the accuracy of clocks. The pendulum clock uses a swinging pendulum as its time-regulating mechanism. The pendulum’s consistent swings, driven by gravity, allow the clock to maintain precise time. While they increased accuracy, they were intended to be stationary, so played a different role in clock technology than pocket watches.

Modern Clock Technology

The First Wristwatches

The first wristwatches were crafted for women as fashion accessories. For example, Patek Philippe created a wristwatch for Countess Koscowicz in 1868. But some believe the first wristwatch was made for the Queen of Naples in 1810 and its creation is credited to Abragam-Louis Breguet.

During this time wristwatches were mostly worn by women because the watches were delicate and being worn on the wrist made them more prone to the elements.

During the Boer War and World War I, wristwatches became practical for soldiers who needed to read time hands-free which popularized the switch to wristwatches from pocket watches for men. Early 20th-century wristwatches incorporated features like luminous dials and chronographs, aligning with military and aviation needs.

Modern Watch Technology

The first half of the 20th century witnessed the advent of quartz oscillation and atomic timekeeping. Although these technologies were relegated to labs in the beginning, they became the standard that we utilize today. And even though they may come across as space-agey—or so new that they’re detached from their much older predecessors—these modern timekeepers run on the same principles as their ancient brothers and sisters.

So, whether your quartz movement is oscillating, or you’re checking the time on an atomic wristwatch, you’re part of a time-honored tradition. And even though the very first clockmaker remains unnamed, their legacy lives on in our lives today.

Preserving Your Treasured Timepieces

By celebrating the evolution of timekeeping and cherishing antique timepieces, we honor both innovation and tradition. These stories remind us how clocks and watches connect us to our past and guide us into the future.

At Times Ticking, we understand the deep value you place on your antique clocks and watches. Whether it’s repairing a cherished heirloom or restoring a rare vintage find, our expert services ensure your timepiece continues to shine for generations to come.

Times Ticking has been in operation since 1982. We have performed clock repair for customers both locally and nationally. If it Ticks, We KNOW it! Our team of clock repair technicians have a combined experience in clockmaking of over 120 years.

Let us help you preserve history. Contact Times Ticking today for expert clock and watch repairs